I am always talking about bringing in training from the outside, not just a vendor but from another occupation or profession.

I am always talking about bringing in training from the outside, not just a vendor but from another occupation or profession.

As most of you may know I have a theatre background as well as one in training and psychology. My latest brainstorm in the area of theatre is to develop a community theatre based on modern classics, where perfection is the name of the game. You come to one of my shows and you will see what the playwright intended.

I’ve also decided a talk back after the show will give us an opportunity for teachers and students to see a value in live theatre. For those not familiar with the term, a talk back is simply an opportunity for the actors and crew, and audience to interact. Often historical questions are asked and answered. Questions asked about certain actions. Those should be reviewed. The idea is that if a person has to ask the purpose, communication did not take place. The talk back brings a depth of ideas and more information; I always found this to be most rewarding–either as an audience or cast member.

Sounds simple. You and I both know it’s harder to achieve a perfect project result in reality, but not so much if you have the attitude and people to make it work. Let’s see if the process doesn’t sound the same for just about any project on several levels and pick the essential ones.

Second, we hold auditions. Just as in your project, you need to have people who can and are willing to do the job. In theatre, I have a special problem and it’s not just available talent. We both have that problem so we work with what we have–beg, borrow and steal. And if you have to steal–steal the best. Once the best cost me a case of Moosehead beer; he was definitely worth it. He was an award-winning sound producer and he applied his talent and knowledge on my production, which certainly enhanced it. Coerce as gently as possible because the idea is that you want them to attach themselves to your group enthusiastically and dedicate themselves to your mission.

My special problem has to do with area actors who are used to rehearsing three-days a week. That won’t do. Professional theatres don’t do that; they work until they get it right (the good ones anyway). I rehearse several hours Sunday through Thursday initially. And, with tech, there’s more later. Good management (a good assistant director or subcommittee chairman) keeps those not actively working on stage, working on the other parts of the play, keeping them engaged. This tough idea has to be sold during auditions, but most actors agree they could use the help. Make no allowances. Those that want to do it bad enough will make it work. Keep auditioning until you get what you want. It is going to be a big deal. It guarantees results. It makes the players proud and others want to be them. It’s a start.

We have our company: our proud challenged actors, and crew if we have managed to get them yet. Some may have heard we aren’t messing around and want to be a part of the action if they are good enough.

Let’s assume at this point, we have everyone ready to go. Just to let you know you don’t have to be heartless and cruel all the time, allow exceptions once. You can be more flexible but performance in hand trumps promised performance anytime. And, have a back-up plan if you can, but it’s still better to push professionalism. A show takes a limited about time to produce: four to six weeks. After that, its weekends mostly and any other special performances. Don’t change the performances without consulting actors; those that have made it to opening night deserve to have some of their schedule in concrete. You may still get what you want. I don’t care how good your actors are, if they aren’t professional don’t switch roles just because they can do it. They might or might not when the time comes.

What is the primary purpose of our project or, in this case, the play? Should be the first question asked and who it’s for is critical. It is not an exercise, nor a game, or a fun thing to do for a few months. For the professionals, this is their life’s work and reputations; for you actors, it’s part of how they get to be professionals or it’s just fun. For some, it may be as much fun when taken seriously. Therein lies the real problem. Taking it seriously. For professionals, generally no problem, but there are always the demigods. They learn in the end.

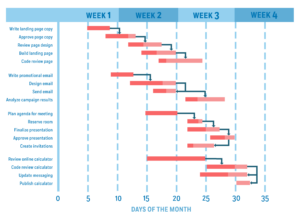

I think that’s enough, but I’m sure you get the idea. The import thing is planning. Know what you need and do not proceed until you get it. You will need certain obvious tools such as a space, a means for good regular communication to take place. Hold out for the best place that works for you. That may mean you need to have your idea fleshed out even more just so you can sell your vision.

Personnel often see it as extra work. Meet with managers and sell your vision so that those personnel asked to be a part of this feel privileged. You may still have to sell the vision through out–even the managers who may have forgotton the vision that didn’t affect them directly.

The simple stuff:

- know what you want

- hold out for what you want

- have a vision you can market even now

- have standards and stick by them, don’t waffle

- continue to sell your vision throughout

- rehearse every change

- and stay proud of your team

—

For more resources about training, see the Training library.

This is mostly from my theatre side. Of course to see all sides, check out my website where I talk even more. Don’t worry – most of it’s coherent. My Cave Man Guide to Training and Development, with its nonsensical approach to the field, continues to do well. Sixty pages or so of sage advice looking at training and development from another point of view for ridiculously low price. My novel (under $4.00), In Makr’s Shadow, is often funny, sometimes serious and poignant; and definitely an entertaining adventure and wit of what happens when Man no longer feels competent to run the world and allows an evolving intellect to take the reins. Both books are available through major producers of e-books as well as the links listed.

Sections of this topic

Sections of this topic